The New Vertical Living Space Embedded with Nature

From eco-villages to vertical gardens, our cities are increasingly turning from grey to green. Introducing a new way of sustainable living that aims to work with nature, welcoming it, rather than banishing it to the peripheries of urban space, Luxiders presents the new vertical living space embedded with nature.

VERTICAL ECO VILLAGE: URBAN LUNG OF BEIRUT

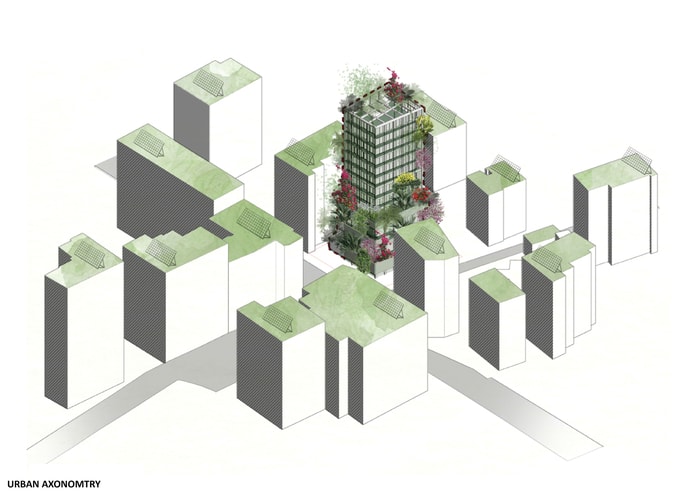

From the creative vision of Anastasia Elrouss Architects, imagining an urban green landmark in the rapidly-developing suburbs of Beirut: the ‘Urban Lung of Beirut’ is a vertical eco-village; encompassing retail, residential and agricultural spaces alike.

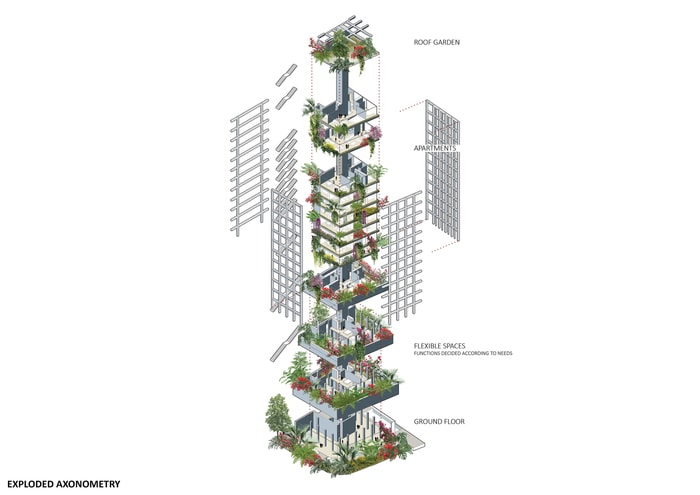

Sat on a 900-square-meter rectangular plot at the intersection between two bustling streets in Chiyah, the MM Residential building encompasses a total built area of 4,500 sq.m, 14 storeys high.

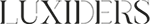

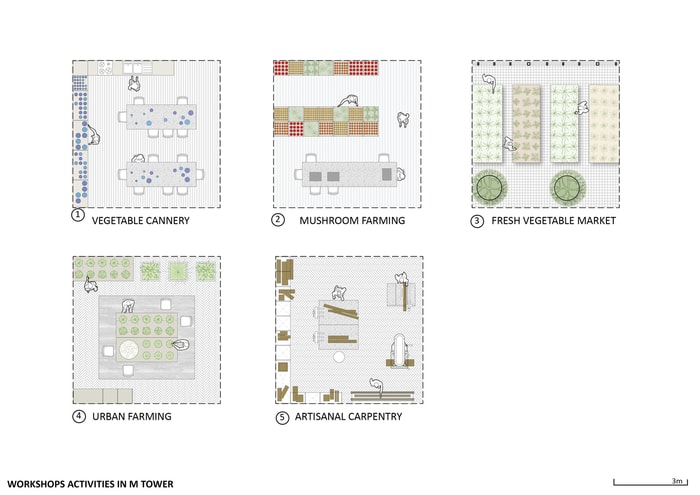

In a bid to advance gender equality in Lebanon, the lower levels, operated by Non-governmental organisation Warchée, intend to feature training and retail facilities. Urban farming areas, comprising mushroom farming, a vegetable cannery and vegetable market would be included. In addition to vocational training and cultural centres, to help empower Lebanese women through building self-sustainable skills in agriculture and carpentry respectively.

Open floor apartment plans designed throughout the mid/upper levels have the capacity to be customised according to the resident’s preference into different apartment configurations: from single-floor apartments, duplexes, penthouses and more. This unique custom-made housing system is inspired by the Lebanese extended family culture and the idea of a vertical village, creating volume through space, instead of being restricted by a set plan.

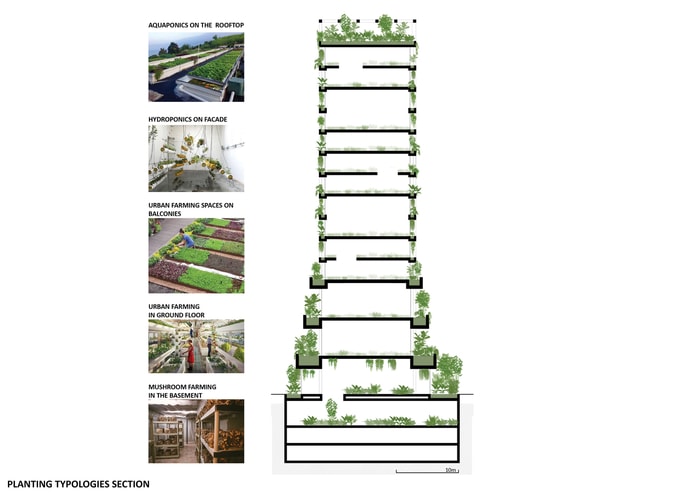

Pocket gardens are peppered between private spaces throughout the building, in the words of Anastasia Elrouss Architects, to create ‘internal privacy for its inhabitants’. Furthermore, vertical terraces wrap around the building’s exterior, to act ‘as a sustainable activator for greener links between the street and the roofs’.

HOW IS IT SUSTAINABLE?

The ‘Urban Lung of Beirut’ was evidently created with environmental responsibility in mind. So-called by its ability to suck carbon dioxide from the atmosphere via photosynthesis, owing to its abundance of plants, the ‘Urban Lung of Beirut’ helps eradicate harmful airborne pollutants within the Chiyah district.

The tower is additionally equipped with photovoltaic and thermal solar shields, able to generate solar energy and heat water during the day. In order to produce power sustainably, without compromising the well-being of our planet by contributing to climate change.

To limit the use of water, the tower includes a rainwater harvesting and storage system, in addition to a space for natural underground water storage for both irrigation and domestic use. This aims to address the immanent global issue of water scarcity, particularly in the Middle Eastern regions known to face drought.

In order to make the tower’s agricultural production wholly sustainable, the lower level urban farms are complemented by two other satellite location: Beirut Park’s renovated wooden pavilion and an urban farm, of which are connected to one another via an electric shuttle.