Solimán López | Memory, Identity And Environment

Solimán López’s work moves restlessly across landscapes —physical, technological, and biological— investigating how we encode memory, identity, and our impact on the environment. In recent years, his projects have taken him from the Arctic to the Amazon. We interview him.

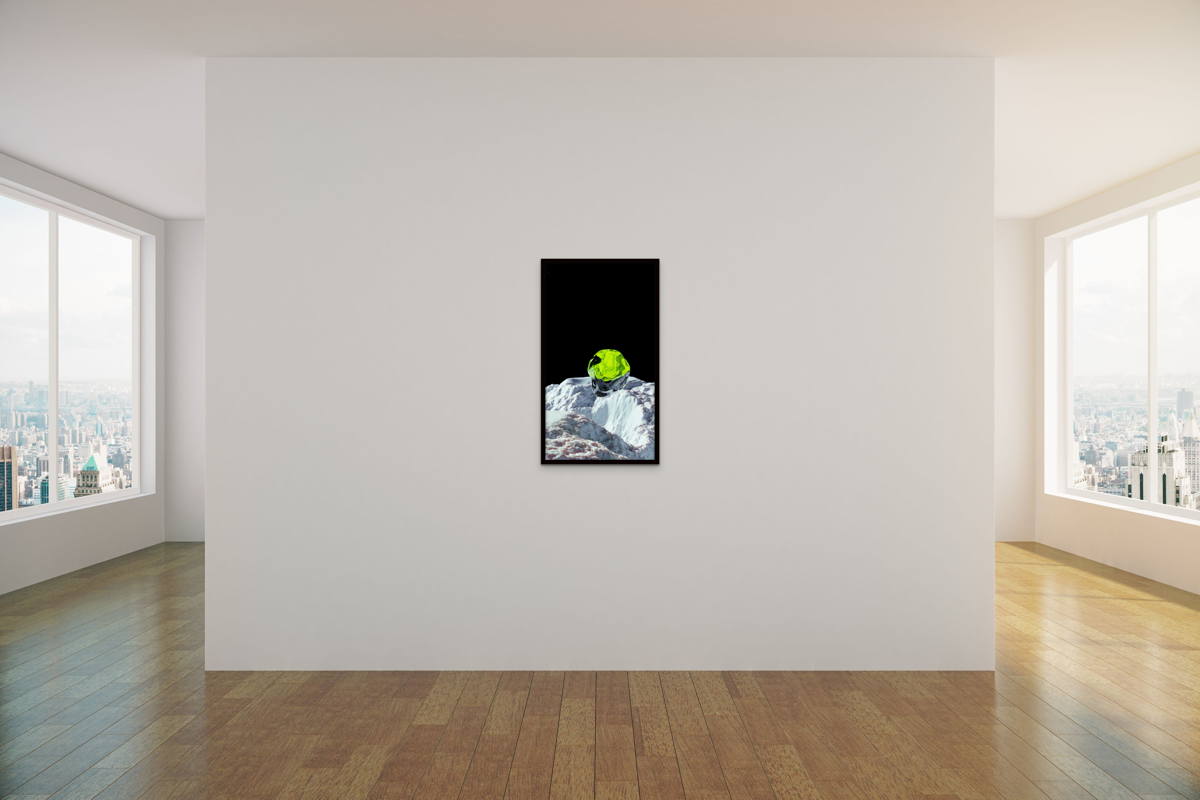

In recent years, Solimán López‘s projects have taken him from the Arctic to the Amazon, resulting in pieces like Manifesto Terrícola, a manifesto stored in DNA molecules inside a 3D-printed collagen ear buried in a glacier; Capside, which preserves local tree DNA in resin spheres to create a dispersed museum in Colombia; and Invisible Pegaso, which imagines using extremophile bacteria and glacier water to break down electronic and orbital waste.

As the founder of the Harddiskmuseum, a project that questions the value and preservation of digital art by housing an entire museum on a single hard drive, López continually explores the intersections of technology, nature, and human memory. He recently presented his new album Ear-thertz, an upcoming release that blends digital art, sustainability, and AI-generated music by turning DNA sequences into sound.

In this conversation, we follow his journeys and thoughts on digital NFTs, the complexities of making art in the midst of a climate crisis, the evolving idea of ownership in a digital culture, and why listening to rivers or encoding art into living matter might open up new ways to reflect on our place in the world.

Interview With Solimán López

Recently, you presented some of your latest works, such as Manifesto Terrícola, Capside, and Invisible Pegaso, created in places as diverse as the Arctic, the Andes, and the Amazon. How was it to bring these projects together in one space and share them through a format that combined digital art, sustainability, and generative music with AI?

It was a collaboration with Siroco Artlab that I saw as a fantastic opportunity to support this new initiative in Madrid. I wanted to explore how a space historically linked to electronic music could be transformed into a venue open to digital art. I presented a selection of my most conceptual projects from the last three years, from Manifesto Terrícola to my work in the Arctic and the Amazon — places you only travel to driven by a very specific interest. It felt important to share these experiences in person in Madrid, to tell their stories, to convey what I lived there. We showed digital pieces adapted to the venue’s screens, and I also premiered a first fragment of my new album, which I’m finishing this summer: a sonification of the DNA sequence used to store Manifesto Terrícola.

Can you explain how the sonification of the DNA works?

DNA is a chain made up of four components (adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine: A, T, C, G). What I do is to take that sequence, turn it into a score, and translate it into sound using instruments. This score literally represents the Manifesto Terrícola encoded in DNA: the text was converted into actual DNA molecules and stored in a collagen ear that we took to the Arctic. The album transforms that sequence into a sonic experience, allowing the audience to “listen to” the manifesto from a different perspective, not verbal or textual, but bodily and sensory.

What is the character of your upcoming album Ear-thertz? What kind of sonic experience does it offer?

It’s very experimental, atmospheric and spectral, with moments of percussion, others that are more ambient, and some fragments generated by artificial intelligence from the manifesto text. It doesn’t follow the traditional logic of contemporary or melodic music. The score is completely organic, somewhat irregular and unique, much like DNA itself.

In your project Invisible Pegaso you talk about concepts like bioleaching as a method to break down electronic waste. Could you tell us what’s this about?

Bioleaching is a process I discovered, interestingly enough, at the Río Tinto. There, a natural oxidation phenomenon turns the water red, linked to the extraction of heavy metals from minerals. It’s one of the major discoveries in biomining. Certain extremophile bacteria have the ability to digest materials and separate metals from other components. They typically do this with rocks, but the same process can be applied to the plastics that cover copper in electronic circuitry. I found this metaphor especially compelling to connect with Invisible Pegaso, a project that speaks about the deterioration of glaciers, but also explores ideas of colonisation and decolonisation.

How does this idea of colonisation come through in your work?

I traveled to Ecuador, to the Chimborazo, the point on Earth closest to the sun, where the hieleros, indigenous families, still extract glacier ice that’s over 6,000 years old, containing oxygen, microorganisms, and atmospheric data. True capsules of geological memory. This practice, a legacy of colonialism, led me to reflect on how Ecuador has also embarked on its own colonising projects, like the CubeSat Pegaso satellite. After only three days, it became space debris, joining the more than 300,000 fragments now orbiting our planet.

The metaphor I propose is that, in the future, extremophile bacteria could help us recycle these satellites, even using glacier water as a medium for dissolution, preventing Chimborazo from turning into a copper volcano because of our technological waste. This project, developed together with Andréz Zábal, resulted in the documentary Invisible Pegaso. The Extreme Satellite, a work of bioart, biotechnology, and climate change, which will be available online in the coming months.

Many of your projects work almost like experiments with an initial hypothesis, where the process seems just as important as the result. How do these ideas come about?

There are many ways. Sometimes opportunities emerge directly from the territory itself, as happened with several of my recent works, driven by life circumstances or by people with projects in those regions who saw me as the right person to explore certain themes. Then there are strong intuitions. I sensed that extremophile bacteria could survive in glaciers, and we confirmed it, or that it was possible to store digital information in glacier DNA in a sustainable way, which we validated scientifically using collagen. There’s also environmental DNA, much of which floats in the air, and what we call “flying rivers”, released by trees as they transpire. These are intuitions that art pushes me to verify scientifically, leading me to involve scientists and experts from different fields to test them.

Now I aim for my work to be a 360-degree exercise, impacting science, society, ecology, and of course, art and aesthetics. This creates multiple layers, from the technical, which responds to the hypothesis, to the visual, which is entirely mine, and the environmental, which cuts through our everyday reality. Out of this convergence arise organic, open projects that aren’t closed off once exhibited. I don’t create works that end with a series of photos or paintings, instead, I keep revisiting, developing, and reinterpreting them over time. Technologically, they remain alive, allowing me to see them from new perspectives as time goes on.

What stages does your creative process usually involve?

I usually start with a theme I want to explore, looking for a key element of our society that can work as a metaphor. On a recent trip to Puertocarreño, on the Colombia-Venezuela border, I found a river that has unintentionally become a geopolitical line. That’s where the metaphor began. How a natural flow turns into a psychological barrier. From there, I look for what I call “thought pivots.” In this case, it was two massive electrical towers meant to link Venezuela and Ecuador, a project abandoned due to politics. The cable still hangs over the river, and I imagined turning that obsolete structure into a symbolic infrastructure.

My idea is to use one tower to support a vine with a beacon that collects river data, feeding an AI that generates a dialogue between the two banks. What’s spoken on one side would be amplified on the other, letting the river speak for both peoples. That’s my process: identify a real issue, translate it into a technically and structurally meaningful installation, and shape it into an artwork with a sociopolitical lens. Over time, my works have developed a distinctive language — color charts, diagrams, audiovisual pieces, photography — elements that recur and define my practice. Like any experiment, there’s space for error; embracing uncertainty and letting the work evolve is essential.

In works like Invisible Pegaso or Olea, you reflect on human impact on both the natural and digital environments. What role does environmental awareness play in your artistic practice?

Many artists are addressing environmental issues, but I think we’re still approaching them somewhat superficially. I worry that it’s becoming a trending topic in contemporary art, driven by an institutional ecosystem that rewards talking about climate, sometimes without real depth. The risk is that we end up trivialising the crisis, speculating more on the discourse than on action itself. Even so, it’s urgent to keep working on these questions. Beyond the planet’s natural cycles, phenomena like global warming or melting ice are clear effects of human activity. And it goes further, we already have microplastics in our brains, lungs, and sperm. That’s not about temperature, it’s about the massive damage we’ve done to ecosystems. There’s not much debate left. The impact is real and widespread. In my work, I try to approach these issues creatively and with a constructive mindset. Technology has brought us to certain limits, but it can also help us understand them, reverse them, or at least give Earth a chance to heal. Why not imagine putting the planet on pause so it can bloom again? That kind of reflection, blending science, ethics, and poetry, runs through pieces like Olea or Invisible Pegaso, where I try to turn critical thought into a sensitive experience, connecting art, science, and environmental awareness without slipping into defeatism.

How do you find a balance between using technology and maintaining a commitment to sustainability?

There are more and more initiatives like Art of Change 21 that aim for a more ecologically conscious artistic practice. But finding balance is hard. In contemporary art, giving form to ideas always has an impact. Digital art isn’t innocent either, it consumes huge resources. And if it’s not digital, you make it a painting, which involves materials, transport, storage… everything leaves a footprint. There’s also something authoritarian about “owning” an artwork. The artist creates an object that circulates, is bought, resold, reinforcing capitalist and globalised logics. When people criticised the environmental impact of blockchain or NFTs, I thought: and how much does a fair like Basel pollute? How many flights, carpets, paints, and tons of wood does it require?

There are no simple answers. I try to think very carefully before acting, though I know it’s nearly impossible to avoid ecological contradictions. It’s a constant balancing act. I know artists who’ve decided never to travel again, and I respect that. But I also wonder: what if by not moving you miss reaching certain contexts or people? For me, staying still is worse. I’d rather move carefully than not at all.

You’ve reflected on digital identity, the dematerialisation of art, and new formats like NFTs. How do you think the notion of authorship and ownership is changing in this new digital ecosystem?

I believe NFTs have profoundly transformed the concept of authorship and ownership in the digital realm. Technically, they solved key problems like traceability and authenticity, but politically they’ve been very deliberately targeted. Banks and governments have no interest in seeing their currencies displaced by a system they can’t control, just as many galleries lobbied against a market that sidelined them and threatened their substantial profit margins on each sale.

Even so, I think NFTs will come back strong, especially as the digital euro and dollar become widespread. And what will we buy with those currencies? Most likely digital assets. The blockchain also brings something crucial: transparency, with open records that don’t suit the shadow economies that first embraced this unregulated system. In the end, NFTs still offer a powerful way to give value, ownership, and circulation to the intangible, even if art and speculation have always attracted opportunists.

“I think NFTs will come back strong, especially as the digital euro and dollar become widespread. And what will we buy with those currencies? Most likely digital assets.”

A few years ago you launched the Harddiskmuseum, a museum that exists on a hard drive. What led you to develop this project? Can you tell us more about it?

A few years ago, I launched the Harddiskmuseum. The project grew out of a need to give value to the digital and to reflect on the intangible, the things that truly sustain our lives, like health, love, sensations, music, yet often get sidelined in societies obsessed with the material. The digital shares that same nature: we can’t touch it, but it exists and affects us.

I was also interested in questioning who controls the “canvas” of the digital artist. Unlike a painter, who owns their canvas, the digital artist creates on devices and servers that don’t belong to them. So where is digital art actually stored? What is the museum of the 21st century? That’s how the metaphor of the hard drive was born, chosen also for its high-tech aesthetic that recalls buildings like the Pompidou or the Guggenheim.mOver time, I took the concept even further. In 2019 we stored all the museum’s metadata in a DNA molecule, creating an organic backup that turns the artist’s “gray matter” into synthetic DNA that holds the memory of the hard drive.

Finally, looking to the future, what projects are you currently working on, and what new explorations would you like to pursue at the intersection of art, science, and technology?

Right now I’m working on projects that explore how to give “voice” to rivers through artificial intelligence, to transcend the geopolitical borders that nature itself does not recognize. I’m also researching, through quantum computing, what the “Vitruvian man of the future” might look like, shaped by climate change and other forces that are reshaping our societies today.

In addition, I’m preparing an artistic essay on outer space and the inner space of the planet, using it as a metaphor to rethink Earth and how we inhabit it. I’m especially interested in recovering ancestral knowledge in Latin America, convinced that we’re not really inventing new technologies but rather reactivating ancient wisdom. That’s why I want to develop an academic program that connects these ancestral insights with current technologies, so that everything we create is grounded in respect for the Earth and our shared human history.

+ Words:

Belén Vera

Luxiders Magazine Contributor

+ Images:

© Courtesy by Solimán López