Martina Troya | The Ecuadorian Designer Weaving Memory Into Modernity with Paja Toquilla in TOCAS

There are stories that begin with a journey and others that begin with a return. TOCAS holds both. From the streets of Quito to the ateliers of Florence, the Ecuadorian designer Martina Troya has carried a fibre, a memory, and the voices of the women who weave them. Paja toquilla – a material rooted in indigenous knowledge and recognised by UNESCO – becomes, in her hands, a language of identity, resilience, and quiet innovation. We interview her.

What began as a search for craftsmanship transformed into a dialogue across continents: between ancestral hands and contemporary design, between imperfection and intention, between the fragility of a natural fibre and the strength of the women who shape it. TOCAS is not just a collection; it is an act of cultural continuity, a declaration that true luxury grows slowly, breathes with the earth, and carries the labour and dignity of the people who make it. We interview exclusively Martina Troya, the 22-years-old fashion designer weaving memories into modernity.

Interview with Martina Troya

Studying in Italy and being surrounded by its culture, fashion, and history was always a dream. This is why Martina Troya chose Florence, home to the artisans and manufacturers behind major fashion houses. Living there led her into the world of craftsmanship. Yet studying abroad also made her appreciate what she had back home. That is why, for TOCAS, she wanted to bring something truly representative of Ecuador. She has always carried her roots with her, and choosing paja toquilla, a UNESCO-recognized material, became essential.

A defining part of her story is that her origins are in Cuenca. Through her Cuencana mother, a jewellery designer, entrepreneur, and deeply creative woman, she discovered her passion for design. Like her, she admires hardworking, resilient women, and the Toquilleras embody that spirit. Women who, in addition to being mothers, sustain their homes through weaving. With her origins rooted in Cuenca, she feels profoundly connected to them, this is the reason why TOCAS became her way to give voice and visibility to the artisans she admires so deeply.

“Innovation doesn’t always mean finding something new. Sometimes it means recognising what we already have and reimagining it with intention.”

Your collection celebrates Ecuadorian identity as much as your own. How has TOCAS changed the way you see yourself—as a designer, as a woman, and as someone connected to a heritage rooted in ancestral materials like paja toquilla?

It definitely changed the way I see myself, because it gave me confidence, pride, and strength. It showed me that when you truly want something, you can achieve it, it’s a matter of persistence and not giving up at the first challenge. TOCAS made me proud to be an Ecuadorian woman and allowed me to feel, even in a small way, like the women I admire so much.

As a designer, it also changed the way I see fashion today. I realized that innovation doesn’t always mean searching for something new, but rather recognizing what we already have and reimagining it with intention.

When you began shaping paja toquilla into garments rather than hats, what inner shift did you experience? Did working with a natural fibre so tied to land, ecology, and tradition reveal something new about the environmental or cultural value of this material

When I began shaping paja toquilla into garments rather than hats, I experienced a profound internal shift. I had always seen it as a rigid material, something exclusively linked to the traditional hat. But transforming it into a textile revealed its flexibility, its ability to adapt, and its creative potential far beyond what I had imagined. This discovery filled me with admiration, surprise, and a deep sense of humility toward a material that carries so much of our identity. Understanding its fragility and strength made me feel connected to the hands that have woven it for centuries, and gave me a renewed appreciation for the tradition and memory embedded within it.

You describe the process as long, imperfect, and profoundly human. What did imperfection teach you about craftsmanship, about yourself, and about the meaning of luxury in a world where true sustainability requires patience and care?

It taught me that there is art and beauty in imperfection. No flower is ever identical to another; because each one is handmade, none will turn out exactly the same. Every piece reflects the artisan behind it, some weave tightly, others loosely, and sometimes even their mood or fatigue becomes part of the work. That is the beauty of imperfection: each piece is unique, never machine-made or mass-produced. On a personal level, it taught me patience and how to slow down. As creatives, we often get swept up in a fast, ever-changing world, and this process reminded me to appreciate the journey, not just the final result. As a lifelong perfectionist, working with this material helped me let go and enjoy the process itself.

I also learned that true luxury lies in sobriety, delicacy, and intention, not excess. Things made with care follow their own rhythm, and that time is part of their value.

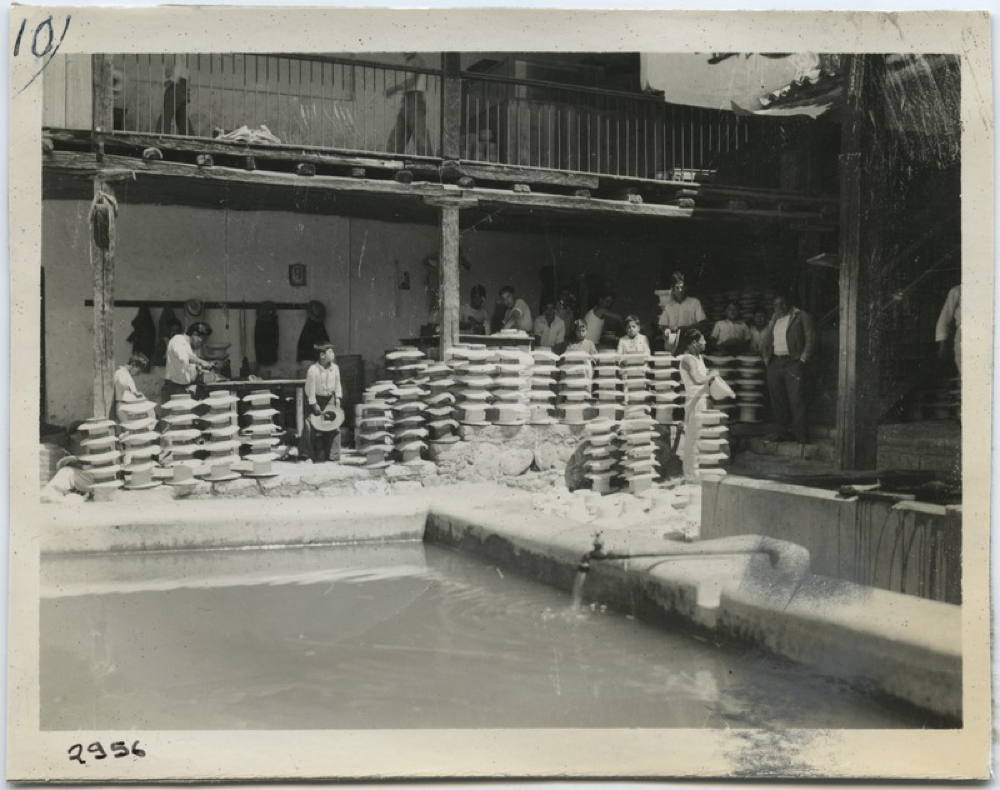

Thirteen years ago, the weaving of paja toquilla was added to UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

The Toquilleras hesitated at first. Who are they in your eyes –beyond artisans– and how did the moment of mutual trust emerge, when you felt you were no longer experimenting alone but co-creating with women who carry centuries of indigenous knowledge?

To me, they are hardworking, admirable women. It wasn’t easy for them to build confidence, to recognize how skilled they truly are, or to overcome the fear of trying something new. But the moment I told them that I trusted them more than they trusted themselves, and that it didn’t matter if something went wrong as long as they tried, a mutual trust began to grow.

Connecting with them on a human level, never judging failed attempts but seeing them as part of the process, allowed everything to flow. We joked, looked for solutions together, and I encouraged them to try again rather than demanding results. That approach made them feel safe and willing to explore something different. It wasn’t easy, especially because I couldn’t be there physically, but through calls where we laughed at the failed attempts and celebrated the new successes, we were able to build a real connection.

Each of the 3,000 flowers in your collection was handmade by a woman in Cuenca. When you held them in your hands in Florence, far from home, what did you feel you were carrying—craft, memory, environmental responsibility, or even the economic hopes tied to their labour?

When I received the flowers in Florence, the first thing I did after opening the box was smell the paja. My entire apartment filled with that scent, instantly transporting me to Cuenca, to the countryside and to the artisanal markets. Holding each flower, feeling the delicacy of the weave, made me admire even more the hands that created them and reminded me that all the insistence and encouragement had been worth it. It also made me feel proud and amazed by what Ecuadorian craftsmanship can achieve, I couldn’t stop feeling the flowers. When you have something in your mind and finally hold it in your hands, the feeling is indescribable: a unique mix of happiness and deep satisfaction. It felt like having a small piece of home with me in Florence.

In my hands, I was carrying craftsmanship, memory, new challenges, and perhaps even new opportunities for the Toquilleras and for Ecuadorian craftsmanship.

Some garments take hours, others take months. How long does it truly take to create one of your pieces, and how does this slow, patient rhythm challenge modern ideas of value, especially considering the socio-economic impact it has on the communities involved?

The flowers arrived gradually as the Toquilleras progressed, and completing all of them took around three months, with more than ten artisans weaving. The next step was constructing the dresses, hand-sewing each flower and shaping the pieces on the mannequin, a process I carried out myself in Florence. For one dress that combines natural beige and black paja toquilla, it took about two weeks to weave the ten panels, involving several artisans. The skirt made from a giant three-meter-wide hat was the longest piece, taking around four months, woven entirely by a single Toquillera due to its delicacy. Depending on the piece, each outfit can take two to three months to complete.

The slow, patient rhythm of paja toquilla challenges modern ideas of immediacy. These pieces take weeks or months, reminding us that behind every hour of work is a person’s story. Their value comes from time, dedication, and the dignity of fair, meaningful craftsmanship.

“The slow rhythm of paja toquilla challenges the idea of immediacy. These garments take months. Their value is measured in devotion, not speed.”

“The beauty of imperfection is that each piece carries a story. No two flowers are ever the same, because no artisan ever weaves the same way twice.”

You often speak of an “invisible thread” connecting everyone involved. Can you recall a moment when this collective energy became tangible—when a garment felt more like a shared cultural story, extending from indigenous hands to your own?

The moment I saw the giant hat finished, before it ever became a skirt, was the moment when our collective energy became tangible. Even though I hadn’t transformed it yet, when I received the photo of the completed hat and saw the shape of the brim, my first reaction was, “wow, this is exactly what I imagined.”

When the artisans sent it to me, they wrote, “this is how it turned out,” with a lot of insecurity about the result. Because the brim was so large, it took on an asymmetrical, organic, wave-like shape. But that was precisely the shape I had already envisioned as the perfect silhouette for a skirt. The moment I felt the brim of the hat in my hands, everything we had created together became real, from my initial design, to the artisans’ handwork, to the transformation into the final outfit.

Transforming ancestral craft into contemporary fashion is a form of cultural translation. What fears surfaced while ensuring that this transformation honoured both the traditions of the Toquilleras and the ecological integrity of paja toquilla?

One of my biggest fears was that transforming a traditional material into a new context wouldn’t be accepted or valued, especially since it had never been done before. I worried that taking the traditional hat weave, turning it into crochet flowers, and then transforming those into garments might not be functional, however I was wrong.

I was careful not to alter the natural working process of paja toquilla, adding no other products to reinforce the fiber. Still, I doubted whether it would work because the material is extremely delicate. But through crochet, it gained the structure and shape needed to become clothing.

By respecting its natural process, I ensured that I honored both the Toquilleras’ traditions and the ecological integrity of paja toquilla.

Looking ahead, what impact do you hope TOCAS will have on the Toquilleras, on the environmental and economic future of paja toquilla, and on the global conversation about what true luxury means today?

With TOCAS, I hope to show the Toquilleras the true potential of the skill they hold in their hands. I believe TOCAS has already had an impact by opening possibilities beyond the traditional hat, giving their work visibility and value. I think the collection can influence the future of this material by proving that paja toquilla can be accepted in haute couture, fine, delicate, entirely handmade, while also transforming the future of the Toquilleras themselves.

As for what luxury truly means today, I believe it reminds us that real value lies in human time and in the respect we give to the people who create.

“With TOCAS, I want the Toquilleras to see the magnitude of what they carry in their hands. Their craft deserves global visibility.”

All Images:

© Courtesy Martina Troya