Between Fiction & Future: A City Home To The World’s Population

The film Planet City is provocative and to some extent disturbing, for it envisions a radical, claustrophobic—almost fragile—model of urbanisation: the entire world’s population living in one city that occupies 0.02% of Earth’s surface. In turn, this would allow Earth to re-wild and to continue to support human life.

In an earlier article we have briefly introduced Planet City which, along the trailer, can be found here. This post is dedicated to exploring some of the aspects of the city as discussed by Australian director Liam Young. Likewise, multiculturalism and sustainability have been conjured in the representation of global citizenship led by costume director Ane Crabtree, who has seamlessly unite past and future in a visual epode. Read here the highlights of our conversation with Liam Young and Ane Crabtree for a bigger picture on the dynamics of Planet City.

Residential Mountain

Code Walker

PLANET CITY: A MODEL OF SELF-SUFFICIENCY

Planet City is a self-sustained city home to 10 billion people. Built entirely on technologies that are already here, the city unveils discrepancies between the rapid evolvement of technologies and the outdated political and social beliefs to adopt them. According to director Liam Young, the lack of ideological investment is what is holding societies from creating effective solutions on climate change, which he counteracts with a urban model that is achievable through utter change in mindset and will to restructure modern modes of living. "Ideology rarely evolves at the pace of contemporary technology. Most of the systems that Planet City is based on are what I describe as ‘before culture’ technologies. That is to say that they have arrived in the world before our cultural understanding of what they might mean for us."

“Planet City is built entirely from sustainable technologies that are already here, but that just lack the cultural investment or political will to implement them at scale. To a large extent all of the systems required to mitigate the effects of climate change or even reverse it have existed for years.” — Liam Young.

“Planet City is designed as a closed-loop urban environment. The form of our contemporary cities rely on the fiction of the periphery, that there is some place outside of our cities where waste goes to be forgotten and food and goods are manufactured,” says Liam Young indicating that there’s no such thing as outside. Abolishing these divisions between the city and the dumping place, food waste becomes an element of the city—a local input. “Food waste is processed through bio reactors and converted into fertiliser and fish food and put back into the system.” And adds that the scalability of this method has been consulted with a NASA microbiologist that works with designing closed-loop waste systems for the future of Mars colonies.

Indoor Megafarm

In fact, Planet City has been built overall on speculations developed with acclaimed environmental scientists, technologists and economists; from real calculations; and based on already built sites and systems. Young shares how visiting sites such as “the world’s tallest vertical farm in Dubai, attached to the world’s largest catering facility which has been developed by Emirates airline,” has helped him envisioned realistic models of self-sufficiency. Based on this observation, Young proposes vertical networks of algae canals to produce a staple food source in addition to powering “the city through a network of locally scaled hydro-power stations.” After all, he explains, “Algae is the most efficient food source for converting the sun’s energy into calories.”

The pink glows washing the sky of the city come from the “rows of artificial suns that feed the stacks of indoor farms,” pointing that agriculture is imagined as an urban activity, once again, keeping the process inside of the imaginary boundaries of the city in lieu of places we overlook.

Young’s narrative, as utopian and far-fetched as it may seem, differs from other utopias where “nostalgia for a natural condition we can never return to” dominates. Instead, Planet City “imagines a new landscape sublime that has emerged from intense pragmatism and the embracing of efficiently engineered food landscapes.”

“What comes into focus are not the extremes of this fictional city but the catastrophic models of everyday urbanism.”

Algae Lakes

IDENTITY AND MULTICULTURALISM

Imagining 10 billion people living under the same roof is simply exorbitant. More so it’s to imagine 10 billion people whose cultural, political, ideological and social differences can peacefully find their own place in one city. If today, as always, Earth’s surface has been the battle ground to tear apart the ones different from us, then who could be those living peacefully in Liam Young’s fantastic city? The answer is humans. “They are you, me, and everyone we know,” says costume director Ane Crabtree.

This model of urbanisation abolishes citizenship based on the nation-state imaginaries—where the planet and identities are invisibly divided—and celebrates multiplicity of cultures as an exercise of voluntary global consensus to live altogether so the planet’s surface can re-flourish. In Planet City inhabitants “live, work, cohabitate, and flourish together in a self sustaining city,” affirms Crabtree.

Bot Herder

Nomadic Worker

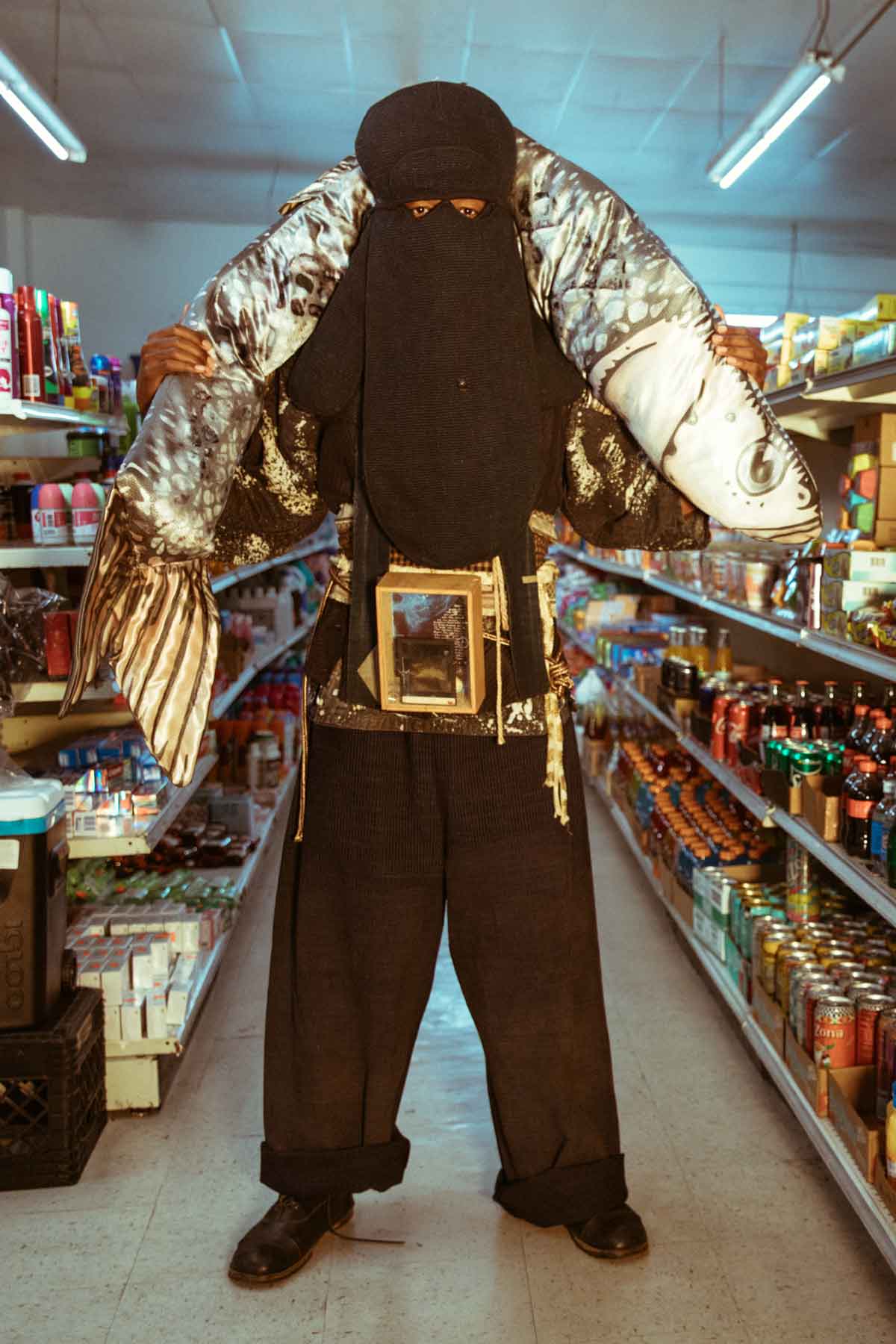

COSTUME NARRATIVES IN PLANET CITY

The film is striking in every single sense—on an ideological and visual level. Citizens appear only now and then, yet their presence is to be remembered: several layers and different materials and styles denote the complexities of the society, one so rich and perplexing that is almost mythical. The citizens, who are found dancing in regular places such as streets and laundry mats, wear staggering garments that refer to tribal, ancestral, animal and modern narratives. “If we think about on ongoing celebration in a speculative, spectacular city, the idea that people are living their lives—some going to and coming from work, some wearing fantastical costumes, as if at a parade celebrating the newly reborn life and culture that co-exists with other cultures side by side—there Planet City resides,” explains Crabtree.

“We meet the people in costume celebrating this new space” — Ane Crabtree

One of the characters has a buffalo head. This has an obvious connection “to ancestral, tribal, and animal symbolism, but it is made new in the world of planet city, where we welcome and embrace the new technology, living alongside this ideology seamlessly, harmoniously.” Thus Crabtree’s costumes do not only bespeak unity but also the placid marriage between past, present and future; technology and nature; reality and mythology.

Zero Waste Weavers

Drone Sheered

Bee Keeper

The materialisation of Liam Young’s concept extended into the costume-making process where worldwide artists with different specialties followed zero-waste practices; dyed with organic tints; repurposed materials; and made fabrics “from literally everything, including the kitchen sink.” Among the artists are Malaysian designer Yeohlee Teng, known for her long trajectory working in sustainable fashion; designer Holly Mcquillan, also known for sustainability; Turkish-American Elanur Erdogan, an artisanal womenswear designer; artist Janice Arnold working with felt fabrics; Lebanese-American Aneesa Shami Zizzo, a textile artist who works with recycled materials; Canadian costume designer Courtney Mitchell; and Ane Crabtree herself, an Okinawan indigenous-American costume designer from LA.

PROMPTING DISCUSSIONS

To Liam Young, the decolonisation of territories is fundamental if we want to continue living on earth. “Although this is a fiction of a form of extreme urbanisation, it is actually arguing for radical deurbanisation in that it proposes to leave 99.98% of the planet for re-wilding and the return of stolen lands. A reversal of the colonialist project.” However, he insists that this alternative to current models of urbanisation is not an attempt to “impose a singular vision but rather the development of counter narratives that could be discussed, debated and scaffold larger scale cultural engagement in their possible implications.”

“Planet City is a fiction shaped like a city. It doesn’t pretend to be an executable proposal, it is a provocation that engages and celebrates the value of fiction as a product in and of itself.”

In discussing the fictional boundaries of his film, he reckons that the type of urbanisation he proposes is as extreme as our current living model which is, conversely, a “live-action dystopian film” that is “just as fantastic, implausible, and incalculable as any science fiction imagining.”

And concludes, “Projects like this one hope to contribute to a necessary collective conversation about the futures we want to all be a part of us. It is a call to arms, a hope that we all will keep making stories and building worlds that become vessels for critical ideas—Trojan Horses hidden within the mediums of popular culture.”

*All images courtesy of Liam Young

+ Words: Alejandra Espinosa, Luxiders Magazine Editor

Liberal Arts graduate | Berlin-based writer

Connect with her on LinkedIn or Instagram (@sincosmostura)