Biophilia | Bringing Nature Indoors

Our bodies’ internal clock is synched to the natural daylight, and our sensorial perception is attuned to spatial configurations in nature. Humans are living organisms meant to interact directly with other living organisms; this interaction provides mutual nurturing—it’s a symbiotic process. An era of dreary concrete walls is shifting our attention back to green spaces. Biophilic design unifies manmade living spaces with nature.

Societies, in the past and present, have shown fondness for nature. Think of the ruins of Pompeii which retain evidence that people brought plants into their living spaces more than 2,000 years ago. Or the rising turn to horticulture for therapeutic purposes where people gather to interact with green landscapes by practicing urban agriculture. The need to coexist with nature is part of our essence.

But the sprawl of urban planning has marked indelible divisions between humans and nature where nature has become alien to our immediate reality and, in many cases—synthetic. Manmade environments, full of concrete, has brought many comforts but costly disadvantages that put at risk our mental health and wellbeing. Many studies point that the expense to live clustered in cities are linked to absenteeism, mental illnesses, impairment in decision-making abilities, insomnia, stress, criminality, among others. This is mainly due to poor ventilation, artificial lightning, and indoor pollution, in other words, due to the dissociation from natural surroundings replaced by artificial environments.

Mandragore, New York © Rescubika

THE MEANING OF BIOPHILIA

The term biophilia was popularised by biologist Edward Wilson in 1984, who described it as “the urge to affiliate with other forms of life.” Wilson knew it well—what’s human life if detached from life itself? Hence the term. In latin, bio means life, and philia love. Love for life. Biophilic design purposely arranges natural elements in a way spaces become a refuge for people to find shelter and peace. It consciously enhances the connection to nature by placing wood objects; green walls with plants; indoor water bodies; and lights mimicking daylight and temperatures.

Using direct presence of nature, biophilic design is developing multi-sensory interactions that are meant to create restorative spaces for humans whilst decreasing air and visual pollution levels in the city. A study revealed that biophilia can increase employee wellbeing by 13%, reduce criminality rates, improve patient recovery times in hospitals, and enhance learning ability in schools. Many companies are investing in the employees’ wellbeing. Adidas and Google are known for actively boosting their employees’ performance; their offices sprout biophilic design.

indoor garden, Hero Switzerland © Biofilico

Hospitals, and schools are refurbishing their installations for the same reason—that of creating environments that help people cope with modern housing and models of productivity. Take the instance of the green wall standing at the University of the Cloister of Sor Juana, Mexico, which contrasts building façades with direct use of plants that mimics organic forms of nature. The visual effect stirs up a sense of refuge in students and passers-by. Or the future Magdi Global Heart Centre Cairo hospital in Egypt which, as revealed only a few weeks ago by the firm Foster + Partners, besides planned to maximise natural light, it will have a roof floor featuring extensive greenery and a view over the lake and the Egyptian pyramids. The design aims to improve the healing time of patients.

Magdi Global Heart Centre Cairo Hospital © Foster + Partners

© Foster + Partners

Even architecture firms are finding ways to merge buildings into nature with the aim to reunify somehow man and nature, as the Norwegian firm Snøhetta intends by embedding architecture in landscapes. Or the vertical living spaces, like the famous Bosco Verticale in Milan and the future Urban Lung of Beirut, that turn grey hollows into green dwellings. A different case of biophilic architecture is found in the Thorncrown Chapel, located in the U.S. The wood sanctuary is built in the midst of a green field, and its glass walls and dim lights allow nature to enter the chapel and be omnipresent to the prayers.

© Thorncrown Chapel

© Thorncrown Chapel

Bosco Verticale, Milano

What comes next is a hefty sprout of biophilic design, which is going to take place faster due to the covid-19, an air-transmission pandemic that demands for high quality air filtration and overall healthier building design, as rising restrictions are blurring the boundaries between living and working spaces. In fact, at the turn of the century, the World Health Organisation claimed that mental disorders and cardio-vascular diseases would figure among the main drivers of health impairments by 2020. The WHO had it well predicted—2020 has been the year to unveil all the disadvantages of living among piles of concrete. Although the pandemic has highlighted the urgency to create spaces that feel more organic to our senses, this has been a concern for a while since modern lifestyles are tailored to stay indoors. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Americans spent over 90% of their life time indoors, meaning that indoor air pollution is up to five times worse than outdoor pollution. This, parallel to the unavoidable shift to work from home, biophilia shows potential to forge spaces that can contribute to mental distress and air cleansing.

© Biophilia Matters

© Biophilia Matters

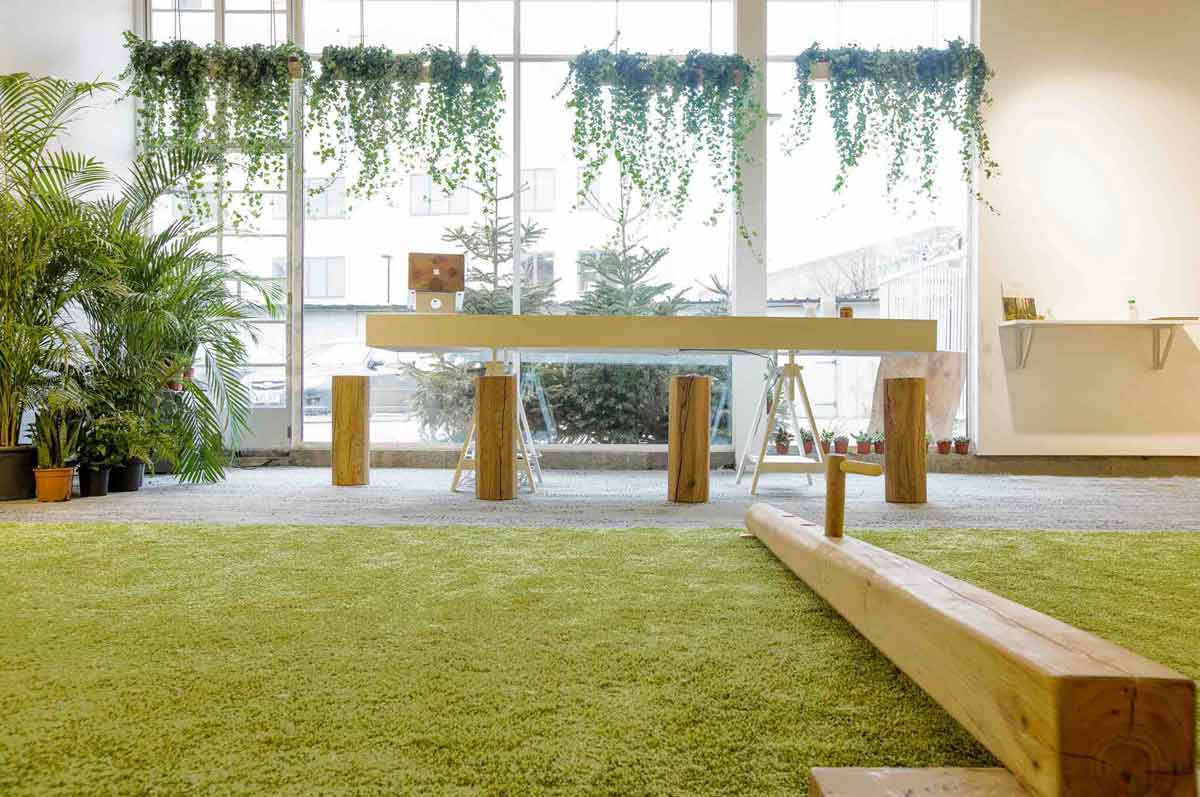

Design studios are developing transportable biophilia artefacts to refurbish interiors easily. Biophilia Matters, a studio in Amsterdam, specialises in manufacturing modular biophilia and urban farming that enable mutual benefits for the environment and human health. Biofilico, a studio operating in London and Barcelona, similarly builds green interiors in offices and gyms, using plants, natural shapes, patterns, scents, sounds and circadian lighting, producing a hybrid atmosphere where nature and manmade structures converse.

© Biofilico

Likewise, biophilic design, or sustainable architecture, aims at decreasing the levels of carbon dioxide by prioritising the use of timber and solid wood panels over steel and concrete, whilst embedding greenery that improves air quality. There is already a long list of proposals queueing to erect biophilic buildings. Earlier this week, the French architecture firm Rescubika unveiled their plans to build the world’s tallest residential tower in New York—the Mandragore—which embeds lush vegetation and would be extensive enough to eat up more carbon than it would generate. The future of the city is spelled out: less concrete, more green.

© Rescubika

*Header image by Biophilia Matters.

+ Words: Alejandra Espinosa, Luxiders Magazine Editor

Liberal Arts graduate | Berlin-based writer

Connect with her on LinkedIn or Instagram (@sincosmostura)